【Watch Kalakal Online】

Faulkner,Watch Kalakal Online Cubed

Arts & Culture

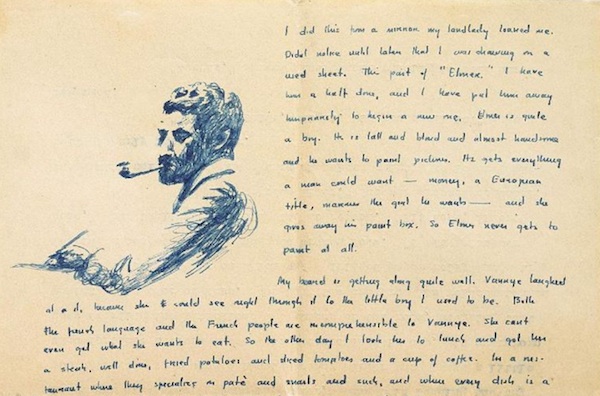

Today, Sotheby’s is auctioning off a collection of sixteen letters and ten postcards that William Faulkner wrote from Europe to his family in Oxford, Mississippi, chronicling his first trip to the Continent in the early fall of 1925. The collection of handwritten correspondence—which includes sketched self-portraits, as well as Faulkner’s musings on growing a beard (“makes me look sort of distinguished”) and dining alone in his hotel room (“here I sit with spaghetti”)—is expected to fetch between $250,000 and $350,000.

The collection seems to provide glimpses of a relatable, human Faulkner: a twenty-eight-year-old who went to nightclubs, griped about money, and signed off as “Billy.” Yet the letters also hint at the profound influence that this trip—specifically, the modernist painting Faulkner first saw in Paris—would have on his fiction. In a letter dated September 22, 1925, he writes, “I have seen Rodin’s museum, and two private collections of Matisse and Picasso (who are yet alive and painting) as well as numberless young and struggling moderns. And Cézanne! That man dipped his brush in light …”

Faulkner in Paris, 1925.

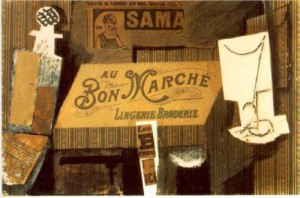

Faulkner himself had an eye for art and a flair for visual expression; he drew and painted as a young man. And Picasso’s (and his contemporary Georges Braque’s) cubist project resonated with him. Beginning roughly after Picasso’s revolutionary Les Demoiselles d’Avignonin 1907 and ending about 1912, Picasso and Braque mainly produced paintings now classified as analytic cubism, representing a subject from multiple perspectives simultaneously. In May of 1912, Picasso glued a piece of oilcloth, printed with a pattern of woven chair caning, onto a canvas he had painted with a still life. Synthetic cubism—the incorporation of found objects in a work to create a modernist collage—was born. (It died two years later.)

Pablo Picasso, Au Bon Marche, 1913.

Some critics argue that Faulkner deliberately modeled the structure of his earlier works, like The Sound and the Furyand As I Lay Dyingalong analytic-cubist lines. Just as Picasso and Braque fragment their canvases in an attempt to capture the subject from many perspectives at once, Faulkner shifts his narrative voice from one character to another, surrounding the plot from all sides while interrupting its flow. But little attention has been paid to whether Faulkner continues to trace the cubist trajectory in his later work (or, put differently, whether cubism remains a helpful interpretive framework for Faulkner’s mature fiction). Was he a synthetic cubist, too?

Recent findings continue to shed light on this. In later novels such as Absalom, Absalom!andGo Down, Moses, Faulkner excerpts texts—such as letters, plantation ledgers, and diaries—which he presents as written by characters within the realm of his fiction. In 2010, Sally Wolff-King, a professor at Emory University, made a surprising discovery: the ledger that Faulkner featured prominently inGo Down, Mosesis heavily based on, and in some sections, nearly identical to, an actual plantation diary—the diary of Francis Terry Leak, a nineteenth-century plantation diary also known as the Leak papers. Wolff-King writes that many names, dates, events, and anecdotes from the Leak papers remain unchanged in Faulkner’s novel.

Why Faulkner, who appeared to delight in discussing his creative process, chose to keep this source under wraps remains unclear. But Wolff-King gives us the missing piece to the literary cubist puzzle: Faulkner’s splicing of found historical texts into his fictional narrative is analogous to Picasso’s gluing an oilcloth to his illusionistic painted canvas—both gestures can be considered forms of synthetic cubism. Faulkner, then, produced self-conscious literary collage.

Why Faulkner, who appeared to delight in discussing his creative process, chose to keep this source under wraps remains unclear. But Wolff-King gives us the missing piece to the literary cubist puzzle: Faulkner’s splicing of found historical texts into his fictional narrative is analogous to Picasso’s gluing an oilcloth to his illusionistic painted canvas—both gestures can be considered forms of synthetic cubism. Faulkner, then, produced self-conscious literary collage.

The notion of Faulkner’s engaging in literary synthetic cubism isn’t merely an issue of semantics, hinging on abstract theory. Rather, it’s a litmus test for how progressive we might understand Faulkner’s work to have been—and to be. And the question of Faulkner’s relevance is indeed relevant, especially as his letters sit on the auction block.

Lindsay Gellman is a writer living in New York City.

Search

Categories

Latest Posts

This may be the most gloriously brutal J.K. Rowling burn of all time

2025-06-26 17:02Patched Desktop PC: Meltdown & Spectre Benchmarked

2025-06-26 16:56Popular Posts

NYT mini crossword answers for May 12, 2025

2025-06-26 19:10Character AI reveals AvatarFX, a new AI video generator

2025-06-26 16:33Featured Posts

NYT Strands hints, answers for May 5

2025-06-26 18:35Exit the 12th Doctor: Peter Capaldi says he's moving on

2025-06-26 18:22'Big Bang Theory' actor brings #MuslimBan protests to the red carpet

2025-06-26 18:13Alienware M16 Gaming Laptop deal: Save $560

2025-06-26 17:10Popular Articles

We Test a $1,000 CPU From 2010 vs. Ryzen 3

2025-06-26 18:51Scientists face 'nightmare' amid Trump's Muslim ban

2025-06-26 18:39Barbie saves a planet in new comic series, may save ours

2025-06-26 18:01This may be the most gloriously brutal J.K. Rowling burn of all time

2025-06-26 17:32MacBook Air reviews: 4 features critics loved, 4 they didn’t

2025-06-26 17:09Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates.

Comments (2983)

Wisdom Convergence Information Network

Best robot vacuum deal: Get the Roborock Q5 Max for 53% off at Amazon

2025-06-26 18:56Star Sky Information Network

'Irresponsible and irrational:' Aussie startups speak out on Muslim ban

2025-06-26 17:10Highlight Information Network

This may be the most gloriously brutal J.K. Rowling burn of all time

2025-06-26 17:04Information Information Network

Widower's ad looking for a fishing buddy is too sweet for words

2025-06-26 16:38Exquisite Information Network

Trump's national security strategy omits climate change as a threat

2025-06-26 16:28